If God is dead why am I afraid of the bunny?

Nato Thompson

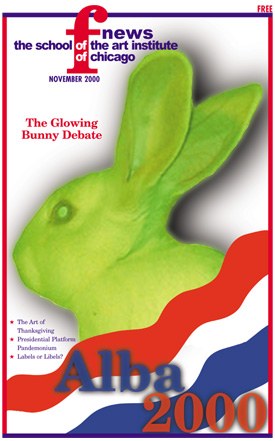

We can all agree that Eduardo Kacís creation of the chimerical bunny known as Alba is a particularly significant moment in art history. The green fluorescent protein, GFP, bunny discussion has been pasted across the news, been on Peter Jennings and now hit a plateau in F-news. Blurring the line between life and art has definitely taken a more literal turn. However, I think we can equally agree that in the history of science this project is just another bump in the road; an historical glowing road kill if you will.

For quite some time now, the biotech industry has been genetically modifying flowers to make them more colorful, removing seeds from fruits and even fraternizing in the ways of making perfect putting greens. The fact that the commercial industry outpaces art in terms of pure aesthetic innovation should hopefully surprise no one. If the combination of art and technology is to have any bearing on culture, it must do so on a level of criticality unavailable in the market place. Sorry visual artists but on that same level advertising has you beat.

This letter came out of discussions that occurred on the Activist Student Union list serv. (see how to join below). Posting emails about Alba got many of us whooped up about a variety of issues that we had trouble articulating and coming to terms with. For this reason, I feel the piece was successful.

While we were excited about discussing the issue of this bunny, it was tempered with the very serious implications that it raises. We, as student activists, are all very concerned about the direction biotechnology is headed. It not only terrifies us, but it points to the serious naiveté by which our culture is facing the future. Not only should art and technology artists talk about the role of capitalist industry in their work, they should be haunted by it. It is for this reason that I feel the piece fails. It seems to lack a sense of pragmatic haunting. |  | Bridging the Two Cultures

Eduardo Kac

Nato's essay generously affords me the opportunity to clarify a few relevant points regarding my "GFP Bunny" artwork. Nato writes that "in the history of science this project is just another bump in the road". Since "GFP Bunny" makes no claim in the scientific realm, and since it is based on well-known scientific processes, the work offers no particularly significant contribution to the history of science. Only in the sense alluded to by C.P. Snow in his famous 1959 lecture, "The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution," in which he presented art and science at opposite poles, can the project be seen as "bump in the road", i.e., drawing attention to chasms and intersections between art and science. I fully agree with Nato's statement that art must contribute a "criticality unavailable in the market place". Equally relevant is the fact there are many different ways through which one can construct a critical perspective. If at first we may not recognize a new critical discourse, this may mean that we have to cognize it. Perception is affected by understanding, which changes in time. I respectfully disagree with Nato's statement that the "GFP Bunny" artwork "lacks a sense of pragmatic haunting". In the context of biotechnology, hardly anything could be more pragmatic and haunting than the direct engagement with the processes of genetic engineering at the level of creation of a higher mammal. What would more directly express the fears and expectations, the hopes and doubts, the sense of familiarity and proximity brought by biotechnology to society at large? All essays in these pages were written with word processors running on computers, both developed by and for the "capitalist industry" Nato alludes to. Does the fact we all use them make us less critical of this industry? "GFP Bunny" is as much a work to be thought about as it is to be though with.

|

Glowing bunnies and animal rights

Lauren Kessinger

When approaching the topic of animal rights, it is important to first establish an ethical base from which to address the situation in question. The basic perception of ethics in regards to the treatment of animals is the sentiment with which you approach living creatures. It is true that animals and humans do not have an equal ability to reason or conceptualize upon their existence.

Animals also do not have the means by which to improve their reality or to reason with the human beings that control their fate. Because of this, we must find the common ground which we humans share with the animals of this planet to answer the question "why should we care at all?" This common ground, which cannot be intelligence or strength (especially in consideration of infants and humans who are mentally or physically disabled and are still deserving of our care and respect), must then be the ability to suffer. And, reflexively, the ability not to suffer, which in humans is called the ability to pursue happiness. Therefore, when questioning the rights of animals we must be conscience of the fact that they can suffer, exactly as we can suffer. Granting rights to animals should be motivated by a desire to reduce the suffering of feeling creatures, rather than on their usefulness to humans.

Keeping this in mind, Eduardo Kac's bunny creates somewhat of an ethical paradox. The bunny, named Alba, seems perfectly healthy and safe despite her phosphorescent fur. In regards to this particular bunny, Iím sure that she is receiving more than sufficient love and care, despite the fact that she exists only for the purpose of being a work of art. And therein lies the ethical dilemma: despite the care she is undoubtedly receiving, artificially creating a life only for the service of human beings is not considering their ability to suffer or their ability to be content. On a larger scale, it can be compared with the millions of animals which are created simply to be killed and eaten without regards to their abilities to suffer.

Am I trying to insinuate that Alba is an argument for vegetarianism? No, I am not. But she does symbolize the greater human attitude that animals are less important than humans are, and that their lives are less meaningful as well as less deserving of respect. Undoubtedly, this bunny will bring more meaning into peoplesí lives than your average pet rabbit. And Iím sure that if they were available, Grateful Dead fans everywhere would be lining up at pet stores for a bunny to match their blacklight posters. However, the position that we should artificially manufacture animals for our personal curiosity, or to create a spectacle, is unethical. A little baby born with kitty cat ears would make a cute spectacle, but the cute kitty cat ears would not help that childís ability to be content, nor to pursue itsí own happiness. Thus, children have not evolved to have furry ears atop their heads.

Genetic research may very well be a medical revolution for our species, and eventually for all species on the planet. Through this science, the possibilities are endless: the irradication of certain diseases and disabilities, healthier fruits and vegetables, perhaps an end to extinction for certain species. But with these benefits comes a responsibility to the lives that are effected, or created: to respect their ability to live a life free of suffering and with the purpose for which they evolved. | | The welfare of transgenic animals

Eduardo Kac

Lauren Kessinger's essay rightly points out, following Peter Singer's pioneering work in the classic "Animal Liberation" (1975), that non-human animals have rights and it is our (human) obligation to safeguard these rights. In the past few years we have expanded the animals rights debate to include the welfare of transgenic animals, which did not exist at the time Singer's book was first published.

As we discuss the welfare of transgenic animals, the key issue is the recognition that transgenic animals have a cognitive and emotional life as rich and as deserving of our love and care as any other animal. It is precisely to draw attention to this fundamental fact that I conceived "GFP Bunny" to start with the creation of Alba and to continue with her social integration as part of my family, where she will have a loving environment in which to grow.

It is out of my love for Alba as an individual that I respectfully disagree with the statement that "she exists only for the purpose of being a work of art." Alba is not a work of art. As I explained in my essay, the "GFP Bunny" project is a complex social event that includes the process of bringing Alba into the world, her social integration, and the dialogue generated by the project. To state that Alba "exists only for the purpose of being a work of art" is to erroneously conflate what Aristotle called "efficient cause" ("the primary source of change") with what he called "final cause" ("the end (telos), that for the sake of which something is done"). In other words: when two individuals who love each other decide to become parents, their love may be the "efficient cause", but the child in their lives does not exist "only for the purpose of" celebrating their love. The child is an individual whose life has its own meaning. Likewise, once Alba was brought into the world, her life sprung with its own meaning.

Lauren wrote that "artificially creating a life only for the service of human beings is not considering their ability to suffer or their ability to be content." If by "artifice" one means with human aid or through human intervention, one needs to consider that Alba is an albino rabbit, a rare occurrence in the wild. It was precisely through human intervention that albino rabbits have been bred and now exist in large colonies. Likewise, equally "artificially" created are roses found in the neighborhood flower shop and offered to significant others as a sign of affection, and happy puppies found in homes everywhere who live fulfilling lives and also bring great joy into the lives of their humans. I do not seek to discriminate between legitimate and illegitimate means of conception. My emphasis is on the fact that once an individual is brought into the world, we must recognize and honor his or her social sphere, in other words, his or her "ability to suffer or to be content".

It seems extremely disproportionate to compare one animal with a loving family with "millions of animals which are created simply to be killed". Lauren wrote that Alba "symbolizes the greater human attitude that animals are less important than humans are, and that their lives are less meaningful as well as less deserving of respect." I disagree. One cannot generalize and equate all genetic selection and transformation. We recently heard through the popular press about the work carried by Dr. Charles Strom, from Illinois Masonic Medical Center, in Chicago. Through pre-implantation techniques, Dr. Strom selected the gender and the health status of a fertilized egg. The objective was for the mother to give birth to a healthy baby boy who could be used as a bone marrow donor to his ill sister. The boy was born healthy; the transplant worked; his sister is already showing signs of improvement. The life of the baby boy is in no way less important or meaningful than any other. Again, the question is not how a life is brought into the world, but the recognition that once a new individual joins the community of life, we must recognize his or her right to live a fulfilling life.

At last, Lauren mentions "the purpose for which they [lives of different species] evolved". The idea that there is a purpose in biological processes is called "teleonomy" The term was coined in 1958 by Colin Pittendrigh to suggest an evolved internal teleology, as distinct from an externally-imposed "teleology". The notion of "purpose" in evolutionary biology is rather problematic. Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela advocate the "elimination of teleonomy as a defining feature of living systems", because they believe this concept does not accomplish much more than revealing "the consistency of living systems within the domain of observation".

In order to further the debate about biotechnology in significant ways, it is imperative to recognize that biotechnology has been a part of culture for millennia (vinegar and beer are the result of early biotechnology). It is also important to recognize that humans have always been an evolutionary force in both human and non-human life. In the twentieth century contemporary medicine and social hygiene practices and technologies have nearly doubled our life span. Humans are part of the ecological system and it is impossible to conceive of a world in which humans do not participate actively. From the perspective of biotechnology, what will determine the future we are collectively building is not whether we will continue to play a role in evolutionary processes of other species, but how we will be able to create a world in which present and future species can be respected and nurtured, irrespective of their unique evolutionary history.

|

New media's prisioner dilemma

Trevor Paglen

Artists involved in 'New Media' are in a real dilemma. If we as individual artists are able to stake out 'New Media' territory for ourselves, and moreover, convince others that this territory is indeed ours, then we can reasonably expect to become 'successful' in the sense that we will be known to others in our field. We are quoted, talked about, and get to invent names for the kind of work that we're doing. Perhaps a certain (small) amount of financial security comes when you are credited with having invented and named a 'new form of art.'

Unfortunately, the imperative to be innovative in the 'New Media Arts' is usually at odds with our role as social critics. When it is necessary for us to be the 'first' to do something, we allow ourselves to be utter slaves to the 'progress' of capital. We lose our ability to think critically about the technology that we are utilizing. We become like rabid Internet start-ups and possessed cold-war politicians in our race to 'be there first' and to out - do the last person. We lose our perspective.

Eduardo Kac is the first man to have created an animal as art, and he has named a new field in art making. Part of Eduardo's piece is his intention to take that bunny home to his daughter and integrate the animal into his family. The bunny will undoubtedly enhance his home with it's presence as a pet. In addition, the GFP Bunny will enhance Eduardo's ability to put his daughter through college and keep a roof over his head when he has retired. Perhaps the GFP bunny piece should have been about this as well. | | Prisioner's Dilemma: from conflict to cooperation

Eduardo Kac

Trevor's is a welcome inquiry into the current phase of transformation in the visual arts, when we expand the now accepted domains of multimedia and networking to incorporate the new processes and issues brought about by biotechnologies. In light of these changes, it is clear that one work by one artist does not warrant the all-encompassing statement that "new media artists are involved in an arms race of cold-war proportions."

In a twenty-year career of exploration of the intersections between art, technology, and society, I have continuously thought to develop and investigate technocultural notions that at first seemed at odds with received and established practices. Following "holopoetry" (1983), I proposed and developed "telepresence art" (1986) and "biotelematics (1994). In 1998 I proposed "transgenic art". The first transgenic artwork I realized was "Genesis" (1999), in which a synthetic gene encodes a sentence from the Bible and mutates on the Internet. In this sense, "GFP Bunny" is not at all a "first", but the most recent work in a two-decade commitment to artistic experimentation and social intervention.

Trevor wrote: "Unfortunately, the imperative to be innovative in the 'New Media Arts' is usually at odds with our role as social critics." This statement seems to paradoxically suggest that the only way to offer valid social criticism is through the use of media pioneered by individuals who are not artists. This is an unproductive paradox because it validates the idea that new media should be left to others, while artists should wait for new media to become standard (as is the case with the computers through which the words in these pages have been written) and only then should they be allowed to make valid social statements with such media.

In my view, the reverse is true. It is exactly when new media remains in the hands of the few "experts" who control its social meaning that the work of artists is most urgent and necessary with these new media. Since artists do not have a stake in corporate biotechnology, and neither do they blindly oppose the presence of new technologies in the larger social context, artists are in a unique position to create subtlety and ambiguity where the dominant discourse oscillates between extreme pro and con positions. In the end, a work of art is not relevant for being the first or the last of its kind, but for speaking to viewers and participants in meaningful ways.

Regarding Trevor's statement that I "created an animal as art", I wish to be clear that Alba is not art. The "GFP Bunny" project is a complex social event that includes the process of bringing Alba into the world, her social integration, and the dialogue generated by the project.

Trevor's concluding remarks seem to suggest that an artist is to be faulted for staying the course, i.e, for his or her uncompromising sincerity and commitment to his or her vision through decades facing adverse conditions, overcoming practical and conceptual obstacles, and developing an audience. As an artist, Trevor must face similar dilemmas and decisions. Taking aesthetic risks is no guarantee of success -- conceptual, commercial, or otherwise. Irrespective of approaches or points of view, one must preserve one's integrity as an artist and citizen. In writing his essay, Trevor took a conceptual risk. I appreciate his courage, and find in it much in common with the spirit that has imbued my own work since 1980.

|